Ground-source heat pump systems utilize the consistent temperature of the ground to heat and cool a home efficiently. A network of underground pipes circulates a mixture of water and antifreeze, which transfers heat to or from the home as needed. This system is highly energy efficient and can also provide hot water.

Direct-use geothermal systems use the naturally warm water from geothermal wells for heating and sometimes for producing hot water. This water is pumped directly into the home and does not require any heat exchange. This system is ideal for homes located near geothermal wells and is often used for radiant floor heating and hot water heating.

What are the pros and cons of a Direct-use geothermal system?

Pros:

High Efficiency: Direct-use geothermal systems utilize natural heat from the earth, making them highly efficient and reducing energy consumption and costs.

Reliable: This type of system is very reliable as it does not rely on any external energy source, such as fuel or electricity.

Environmentally Friendly: Direct-use geothermal systems do not produce any greenhouse gas emissions, making them a clean and environmentally friendly option.

Low Maintenance: This type of system requires minimal maintenance, as it does not have any moving parts and operates underground.

Cons:

Limited Availability: Direct-use geothermal systems are only feasible in certain areas where geothermal wells are accessible, and the water is warm enough for heating purposes.

High Initial Cost: The cost of drilling a geothermal well can be high, making the initial investment for a direct-use geothermal system relatively high.

Limited Functionality: Direct-use geothermal systems are only used for heating and hot water, whereas a ground-source heat pump system can also provide cooling.

Well Drilling Risks: The process of drilling a geothermal well carries some risks, such as the potential release of harmful gases or the contamination of underground water sources.

The cost of a direct-use geothermal system can vary greatly depending on several factors, such as the location, size of the home, and the complexity of the installation.

Equipment costs:

Geothermal Well: The cost of drilling a geothermal well can range from $10,000 to $30,000 or more, depending on the depth and location.

Heat Pump: A heat pump is required to circulate the warm water from the well to the home, and its cost can range from $2,500 to $7,500.

Pipes and Insulation: The cost of pipes and insulation can vary, but it can be around $1,500 to $4,000.

Installation costs:

Installation of the well, heat pump, and pipes can cost between $20,000 to $50,000 or more, depending on the complexity of the project and the location.

It is important to note that these costs can vary greatly and that it is always best to get a detailed quote from a qualified geothermal contractor. Additionally, the high initial cost of a direct-use geothermal system is often offset by long-term energy savings and low maintenance costs.

Heat Pump:

A heat pump is a central component of a direct-use geothermal system. It circulates the warm water from the geothermal well to the home and is responsible for extracting heat from the water and transferring it to the home for heating purposes. Heat pumps come in different sizes and configurations, but the most common types used in direct-use geothermal systems are air-source and water-source heat pumps.

Air-source heat pumps use the outdoor air as the source of heat, while water-source heat pumps use the water from the geothermal well. Both types of heat pumps work by using a refrigerant to transfer heat from one location to another. In the case of a direct-use geothermal system, the heat pump circulates warm water from the well to the home and transfers heat to the home's heating system.

Pipe Insulation:

Pipe insulation is used in a direct-use geothermal system to prevent heat loss as the water is circulated from the geothermal well to the home. The insulation helps to keep the water at a consistent temperature, which improves the efficiency of the system and reduces energy consumption.

There are different types of insulation materials available, including foam insulation, fiberglass insulation, and closed-cell insulation. The type of insulation used will depend on the specific requirements of the system and the local building codes. It is important to use high-quality insulation that is designed for underground use, as it must be able to withstand the harsh conditions of underground installation.

Several types of foam insulation can be used for underground pipes in a direct-use geothermal system, including polyurethane foam and polyethylene foam.

Polyurethane foam is a closed-cell foam that is known for its high insulation value, durability, and resistance to moisture. It is often used for underground pipe insulation due to its excellent thermal performance and ability to withstand the pressure of the surrounding soil.

Polyethylene foam is another common choice for underground pipe insulation. It is a lightweight, flexible, and closed-cell foam that is easy to install and provides good insulation properties. It is also resistant to moisture and has a low thermal conductivity, which makes it a good choice for geothermal applications.

The type of foam insulation used in a direct-use geothermal system will depend on several factors, such as the local building codes, the climate, and the specific requirements of the system. It is best to consult with a professional geothermal contractor to determine the most appropriate type of insulation for your system.

Closed-cell insulation is a type of insulation material that is made up of small, tightly packed cells that are filled with a gas, such as air, or a proprietary blend of gases. The cells are closed, meaning that the gas is trapped inside and cannot circulate freely, providing excellent insulation properties.

Closed-cell insulation is known for its high insulation value, making it a good choice for applications where high thermal performance is required. It is also resistant to moisture, which makes it a good choice for underground installations, such as in a direct-use geothermal system.

Closed-cell insulation is typically denser and stiffer than open-cell insulation, making it a good choice for applications where structural support is required. Additionally, because the cells are closed, it has a higher resistance to air infiltration and can provide a vapor barrier, making it a good choice for applications where airtightness is important.

Overall, closed-cell insulation is a versatile and effective insulation material that is widely used in a variety of applications, including building and construction, industrial and commercial applications, and geothermal systems.

The type of gas used in closed-cell insulation can vary depending on the manufacturer and the specific product. Some of the most common gases used in closed-cell insulation include:

Air: Air is the most common gas used in closed-cell insulation and is often used in polyurethane foam insulation.

Argon: Argon is an inert, colorless, and odorless gas that is often used in closed-cell insulation due to its excellent insulation properties.

Krypton: Krypton is another inert gas that is often used in closed-cell insulation due to its high thermal resistance.

Xenon: Xenon is a rare, inert gas that is used in closed-cell insulation due to its high thermal resistance and insulation value.

It is important to note that some manufacturers use proprietary blends of gases to enhance the insulation properties of their products. These blends can be optimized to provide the best combination of insulation value, moisture resistance, and durability.

The specific gas used in closed-cell insulation will depend on the manufacturer, the product, and the specific requirements of the application. Consult with a professional insulation specialist to determine the best type of gas for your needs.

What are the potential hazards of using geothermal energy production?

Yes, there are potential hazards associated with geothermal energy production, although these are generally minor compared to the benefits of this clean, renewable energy source. Some of the most common hazards include:

Hydrogen Sulfide Gas: Hydrogen sulfide gas is a byproduct of geothermal energy production and can pose a health risk if not properly managed. In high concentrations, hydrogen sulfide gas can be toxic and can cause respiratory problems, headaches, and dizziness. It is important to install proper ventilation systems and monitor hydrogen sulfide levels to ensure the safe operation of a geothermal energy system.

Earth Tremors: Geothermal energy production can sometimes cause small earth tremors, although these are generally minor and do not pose a significant risk. In some cases, geothermal energy production has been associated with increased seismic activity, although this is relatively rare.

Environmental Impacts: Geothermal energy production can have impacts on the local environment, including changes to water quality, soil and air quality, and wildlife habitats. It is important to carefully manage and monitor these impacts to ensure that geothermal energy production is sustainable over the long term.

Corrosion: Geothermal energy production can result in increased levels of corrosion, which can affect the longevity and performance of equipment and infrastructure. It is important to use corrosion-resistant materials and coatings to prevent this type of damage.

Overall, geothermal energy production is considered to be a relatively safe and environmentally friendly form of energy production, and the hazards associated with this technology are manageable with proper planning and management.

Here are a few companies that install geothermal systems for homes in the Dallas, Texas area:

EcoGeo Solutions

TGE Technologies

Skyline Innovations

Green Energy Solutions

Prime Mechanical

Texas Geothermal Solutions

H&H Environmental Services

Texas Renewable Energy

WaterFurnace Southwest

Earth Energy Solutions

Here are a few companies that install geothermal systems for homes in the New York Tristate area:

Advanced Geothermal Systems

Geothermal Experts

Tri-State Geothermal

Earth Energy Solutions

Green Energy Solutions

Energy Geothermal

Infinity Renewables

Climate Control Heating & Air Conditioning

Naughton Energy

R.A. Snyder Services

Here are a few companies that install geothermal systems for homes in the Los Angeles, California area:

Cal-Tech Heating & Air Conditioning

California Geothermal

Geo-Thermal Solutions

Green Energy Solutions

Sunset Air

SoCal Geothermal

Energy Geothermal

Infinity Renewables

EcoGeo Solutions

LA Geothermal Solutions

It is important to note that this list is not exhaustive, and there may be other companies in these areas that offer geothermal installation services. Before choosing a company, it is recommended that you research their experience and reputation and get multiple quotes to compare prices and services. Additionally, it is recommended that you work with a licensed and insured contractor to ensure the quality and safety of your geothermal system installation.

Here are some potential drawbacks of using geothermal energy for a home:

Initial Costs: Installing a geothermal energy system can be expensive, with costs ranging from $20,000 to $50,000 or more. This may make it less accessible for some homeowners, especially those on a tight budget.

Complexity: Geothermal systems are complex and require specialized knowledge and skills to install and maintain. This can make it difficult for homeowners to perform their own maintenance or repairs and may require them to hire a professional contractor.

Location-specific: Geothermal energy systems require access to geothermal resources, such as hot springs, geysers, or volcanic activity. This means that not all homes will be able to use geothermal energy, and the suitability of the technology will depend on the local geography and geology.

Limited Capacity: Some geothermal systems may have limited capacity and may not be able to generate enough energy to power a home during periods of high demand.

Environmental Concerns: Geothermal energy systems can have some environmental impacts, such as the release of greenhouse gases and changes to water quality in the vicinity of geothermal wells. Additionally, the installation of geothermal systems may result in the disturbance of natural landscapes, including the removal of vegetation and the excavation of land.

It is important to note that these potential drawbacks will vary depending on the specific system, location, and other factors. Before choosing a geothermal energy system, it is important to carefully consider the costs, benefits, and potential drawbacks of the technology and to work with a licensed and experienced contractor to ensure the quality and safety of your installation.

Here are some long-term benefits of using geothermal energy to power a home:

Energy Efficiency: Geothermal systems are highly energy efficient, with efficiency ratings that can be as high as 400%. This means that they can generate more energy than they consume, reducing the amount of energy required from other sources.

Cost Savings: Geothermal systems can result in significant cost savings over time, as homeowners can reduce their dependence on more expensive forms of energy, such as electricity from the grid or heating oil.

Reliability: Geothermal systems are reliable and can provide consistent and continuous heating and cooling with minimal maintenance. This means that homeowners can count on their systems to keep their homes comfortable and energy efficient, even during periods of extreme weather or power outages.

Environmentally Friendly: Geothermal systems are considered to be environmentally friendly, as they produce very low emissions of greenhouse gases and do not rely on the burning of fossil fuels.

Longevity: Geothermal systems are long-lasting and can last for decades with proper maintenance. This makes them a smart investment for homeowners who want to reduce their energy costs and minimize their environmental impact over the long term.

It is important to note that the specific benefits of using geothermal energy to power a home will depend on the specific system, location, and other factors. Before choosing a geothermal energy system, it is important to carefully consider the costs, benefits, and potential drawbacks of the technology and to work with a licensed and experienced contractor to ensure the quality and safety of your installation.

What are the potential electromagnetic issues with using geothermal power for a home?

There are no significant electromagnetic issues associated with using geothermal power for a home. Geothermal systems work by tapping into the heat stored in the earth to provide heating, cooling, and hot water for a home. Unlike other types of energy generation, such as fossil fuels or nuclear power, geothermal systems do not generate significant levels of electromagnetic radiation or interference.

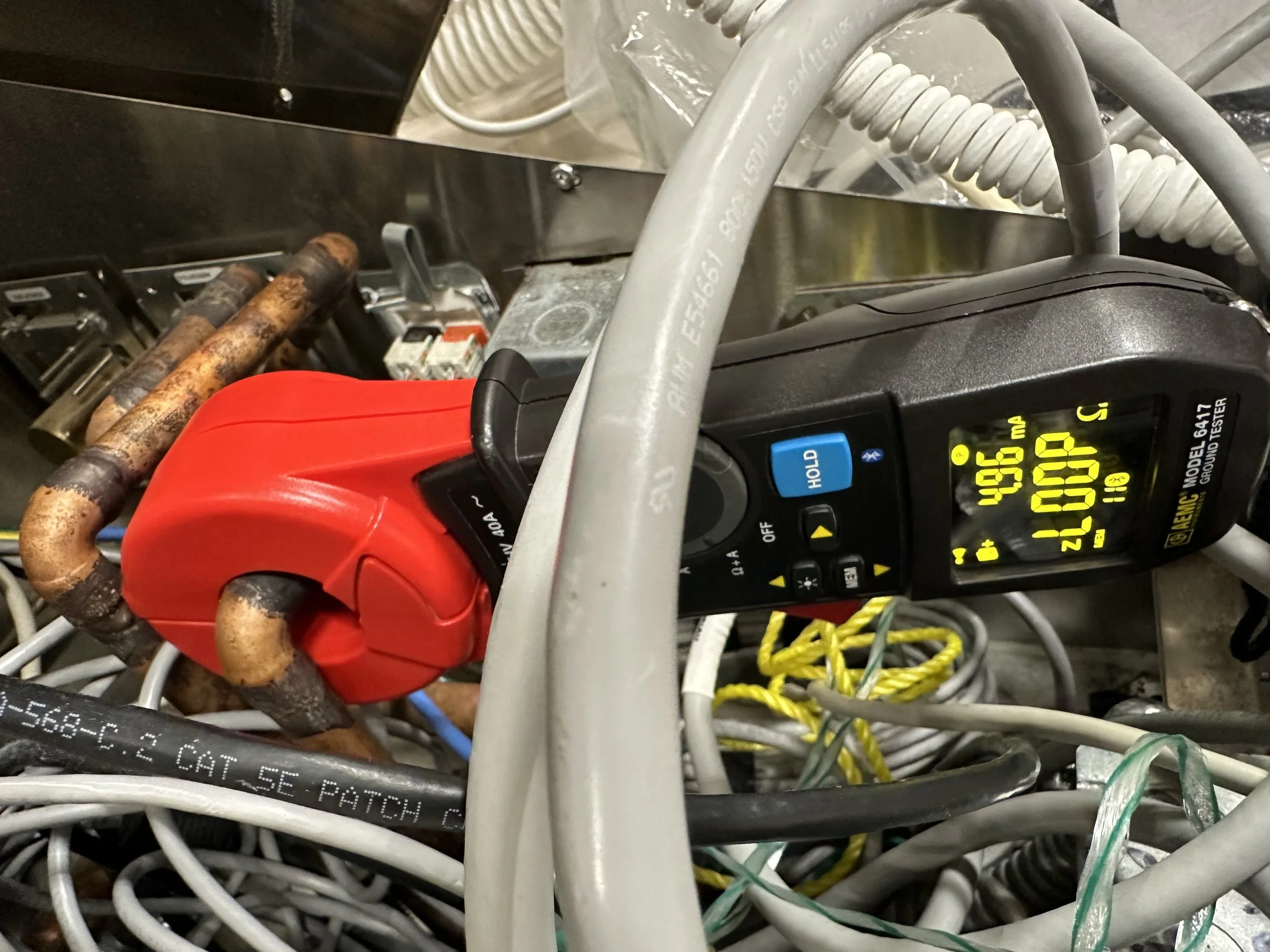

It is important to note that all electrical equipment, including geothermal systems, generates some level of electromagnetic interference, but these levels are typically well within safe limits and do not pose a significant risk to human health or the environment. If you have concerns about electromagnetic interference from your geothermal system, you can work with a licensed and experienced contractor to assess the system and make any necessary modifications to ensure that it operates safely and efficiently.

Are inverters needed to convert DC to AC with geothermal systems?

Inverters are not typically needed with geothermal systems. Geothermal systems work by tapping into the heat stored in the earth to provide heating, cooling, and hot water for a home. Unlike solar panels, which generate electricity from the sun, geothermal systems do not generate electricity and do not require inverters to convert DC to AC.

Instead, geothermal systems use a heat pump to transfer heat from the earth to the home, where it is used to provide heating, cooling, and hot water. The heat pump operates using electrical power, but it does not generate electricity and, therefore, does not require an inverter.

If you are interested in using geothermal energy to power your home, it is important to work with a licensed and experienced contractor who can help you assess your specific energy needs and determine the best type of geothermal system for your home. They can also provide information on any additional equipment or components that may be needed to ensure the safe and efficient operation of your geothermal system.

Does the heat pump use a Variable Frequency Drive?

Yes, some geothermal heat pumps use a Variable Frequency Drive (VFD) to control the speed of the system's compressor and circulate refrigerant. The VFD helps to regulate the flow of refrigerant, which in turn helps to optimize the efficiency of the heat pump and reduce energy consumption.

VFDs can also be used to control the speed of the system's fan or pump, depending on the specific design of the heat pump. By using a VFD, the heat pump can operate at an optimal speed to meet the demands of the heating and cooling system, which can help to improve efficiency and reduce energy consumption.

It is important to note that not all geothermal heat pumps use a VFD, and the use of a VFD is dependent on the specific design of the heat pump. If you are interested in using a geothermal heat pump with a VFD, it is recommended that you work with a licensed and experienced contractor who can provide information on the specific heat pump and assist with the installation and operation of the system.

Does the VFD produce EMI?

Variable Frequency Drives (VFDs) can produce Electromagnetic Interference (EMI). EMI is the result of electrical and magnetic fields that are generated by electrical equipment and can interfere with other electronic equipment or devices.

In the case of VFDs, the fast switching of the power electronics within the VFD can generate EMI, which can affect other electronic equipment or devices in the vicinity. However, most VFDs are designed with EMI filtering to reduce the level of interference, and modern VFDs are typically well within the limits established by international standards for EMI.

If you are concerned about the potential for EMI from a VFD in your geothermal heat pump system, it is recommended that you work with an experienced EMI Consultant who can assess the specific VFD and make any necessary modifications to ensure that it operates safely and efficiently. They can also provide information on any additional equipment or components that may be needed to reduce the level of EMI from the VFD.

What are the typical frequencies of variable Frequency Drives for geothermal heat pumps?

The typical frequency range for a Variable Frequency Drive (VFD) in a geothermal heat pump system is between 0 and 60 Hertz (Hz). The exact frequency range of a VFD will depend on the specific design and requirements of the geothermal heat pump system.

The VFD is used to control the speed of the system's compressor or fan, which helps to regulate the flow of refrigerant or air within the heat pump. By adjusting the frequency of the VFD, the speed of the compressor or fan can be increased or decreased as needed, which in turn helps to optimize the performance of the heat pump.

It is important to note that different geothermal heat pump systems may use VFDs with different frequency ranges, and the frequency range of the VFD will depend on the specific design of the heat pump system. If you are interested in using a geothermal heat pump with a VFD, it is recommended that you work with a licensed and experienced contractor who can provide information on the specific VFD and assist with the installation and operation of the system.